Aidan Lapp has compared sitting in front of him for a portrait to an annual physical. Hold Still, this exhibition’s directive title, extends the metaphor: both portraitist and doctor ask their subjects to remain in position long enough for careful examination (though Lapp admits he only sparingly requests total stillness from a sitter). In the portrait session, as in the exam room, the encounter is diagnostic—a close, sustained looking for changes and details that might otherwise go unnoticed, with the suspicion that they might reveal or clarify something larger. Lapp’s portraits become records of his own community across time; his sitters’ likenesses accumulate year after year, added to their growing file. Since Lapp began making portraits in 2020, each subject has entered his expanding contact book, a log of new proximity and eventual return. Can we consider each first portrait an intake?

Standing among Lapp’s works at Auxier Kline, it is clear that the artist seeks more from portraiture than resemblance. The works, collecting new and returning sitters, are responses to the presences of people he knows, people he will see again. (Recurring visitors to Lapp’s exhibitions will see them again, too, although in a different composition.) The question is not whether each sitter has changed, but how change itself grows visible, and how it is surfaced on paper by Lapp’s hand.

Drawing and painting play distinct roles in this inquiry. While a sitting may take hours, Lapp’s drawings still move quickly, working to keep pace with a body that, inevitably, shifts weight, relaxes and corrects its posture, makes slight adjustments. It is during this phase that the flat page becomes space, and that the space acquires its occupant. In his 1960 essay collection Permanent Red: Essays in Seeing, art critic John Berger describes his experience drawing someone’s portrait, and that, “for a moment, he was no longer a man posing but an inhabitant of my half-created world, a unique expression of my experience.”

Lapp’s drawings seem to recognize a similar dynamic. They are not attempts to arrest a sitter in a fixed pose or to capture them, isolated and complete. The cyclicality of Lapp’s practice—its emphasis on return, on revisitation—abandons this desire for totality. Instead, each drawing marks another entry into Lapp’s orbit. There’s something autobiographical in this, not just because of a visual kinship across the portraits with Lapp’s own resemblance, but because each work registers Lapp’s time spent looking and being-with. As Berger suggests, a portrait becomes an expression of the artist’s experience. Lapp’s subjects are not simply objects of representation in his drawings. With the artist, they cohabit a world realized only through a circuit of presence and creation—of subject and of self—that each act of depiction necessitates.

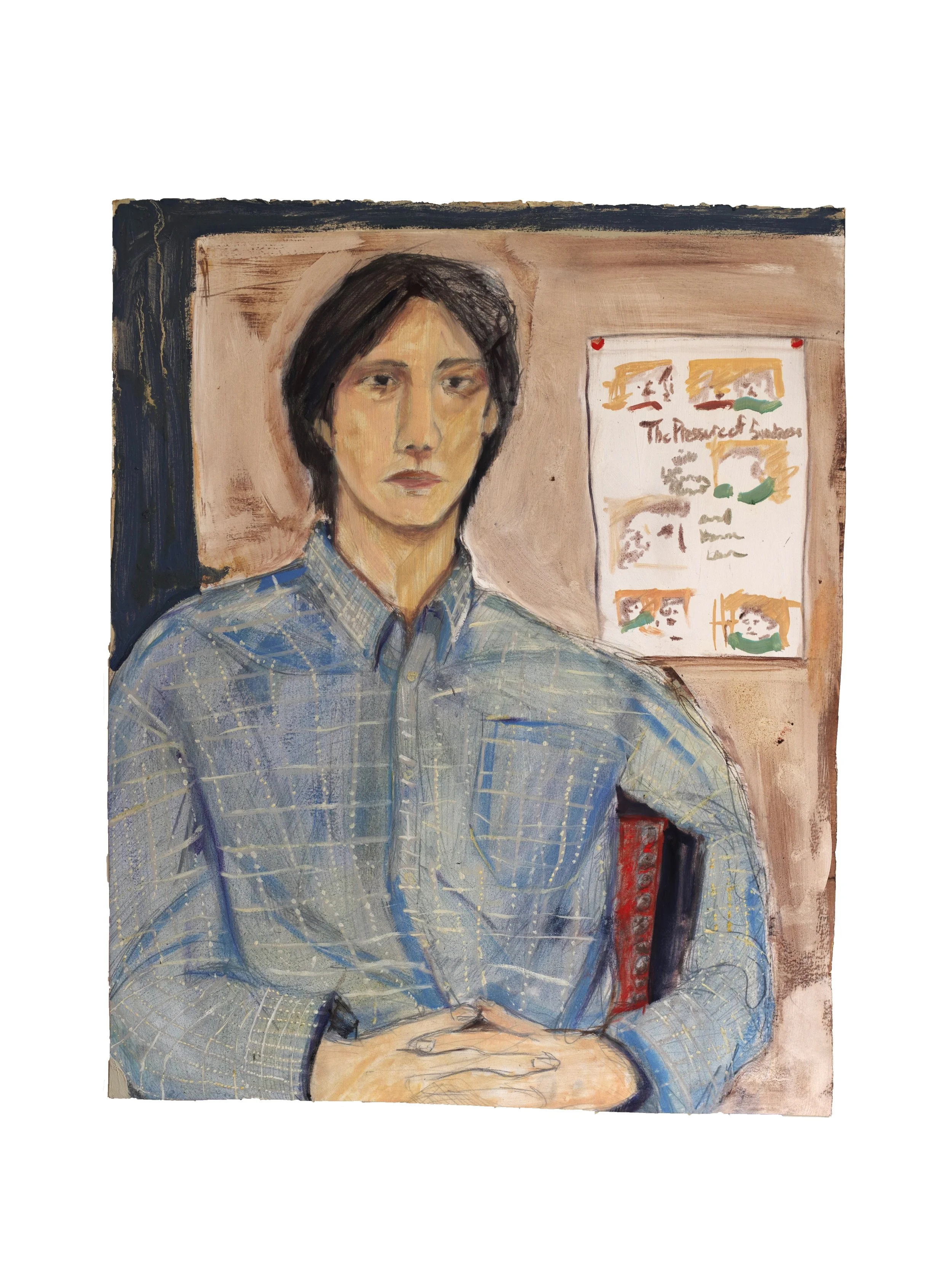

In Wally, this materializes clearly. The planes of shadow beneath the sitter’s eyes, the light gathering along his brow bone, his intent gaze, and the interlocking of his fingers are rendered with an alertness that feels neither incidental nor overly resolved. Each element seems to arrive through contact rather than chance or invention. The drawing does not circle its subject from a distance; it builds him out from a center, mark by mark, until a sense of interiority emerges—if not psychological, experiential. As Berger suggests, Wally is not the result of a man posing but a co-presence, a realization of form shaped by time spent together between time spent apart.

If Lapp’s drawings establish contact, then his paintings contemplate it. Completed later, alone in his studio, Lapp’s painted portraits unfold slowly and meditatively over his on-site drawings. His process allows for observations to thicken and for reflections—made at a distance—to evolve over the impressions that came before. The result is that the figure, already in place, gains its flesh. Tones are calibrated and established, not by direct reference but through sustained familiarity and rumination.

In Isabel in Chinatown, that familiarity registers as warmth. The surface of the painting seems to hold temperature; color breeds palpable intimacy. The closeness established in drawing moves, in painting, from spatial to tactile—something you could press a thumb into, or pinch. Flesh here is not perfect anatomical accuracy, but density through care, a sense that the figure has been breathed into, rather than colored over.

To be clear, Lapp’s drawings are not preparatory sketches, even those which later receive the treatment of oil paint. Instead, they are works in their own right, and as Berger explains, each of their marks brings the artist “closer to the object, until finally you are, as it were, inside it: the contours you have drawn no longer marking the edge of what you have seen, but the edge of what you have become…until you have crossed your subject as though it were a river.

Lapp’s portraits, across drawing and painting alike, trace this passage. They record not only who was seen but how seeing unfolded—where it entered, lingered, hesitated, and ultimately, arrived beyond. Lapp appears at the center of this social world, not as an observer apart but as someone moving into and through each sitting, met, and then changed.

Lapp’s practice resists portraiture that finishes. It proposes portraiture as follow-up: a return visit, a renewed impression, an ongoing record. The works in Hold Still do not ask what a sitter looks like but how a person finds themselves with Lapp—how presence accrues, a relationship deepens, and change, however subtly, leaves its trace. The encounter does not conclude when the sitting ends; it opens a world that remains within reach, provisional, subject to return.

See you next year.

Natalie Ginsberg is an art historian and dancer specializing in performance, dance, and time-based media. She is currently pursuing an MA in the History of Art in the Williams College–Clark Art Institute Graduate Program.

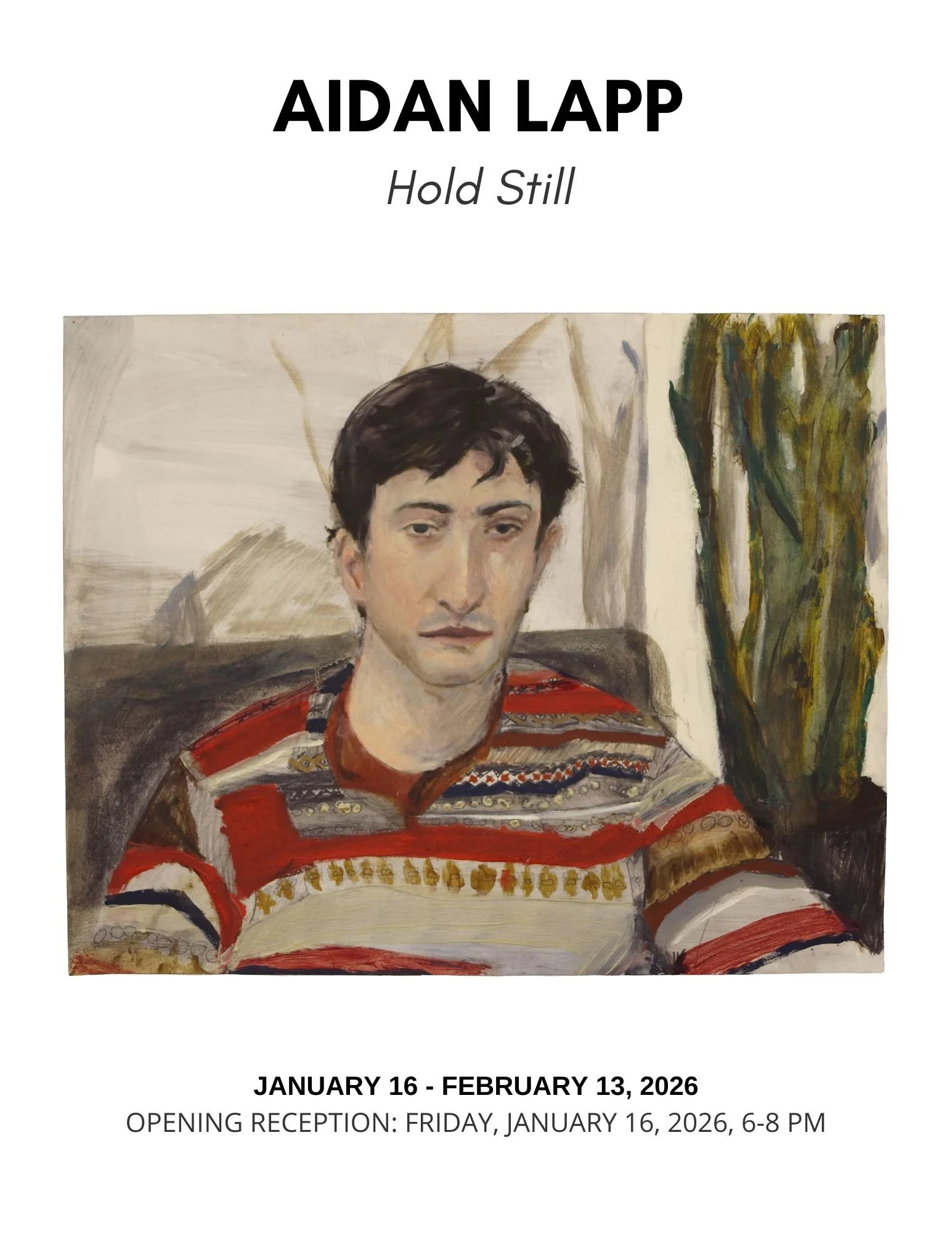

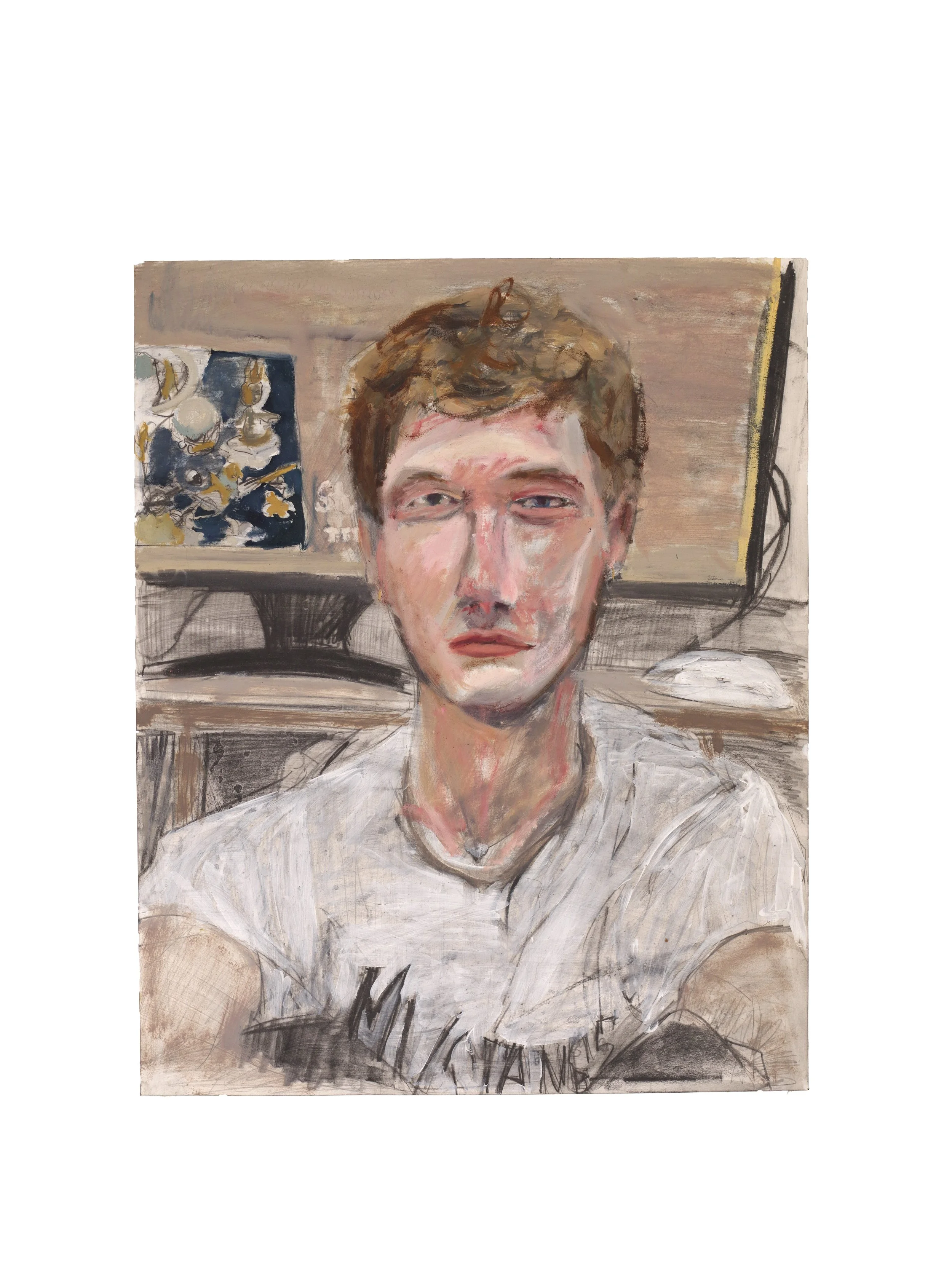

"Issac in Sweater", Oil and Graphite Materials on Paper, 16 x 20 inches, 2025

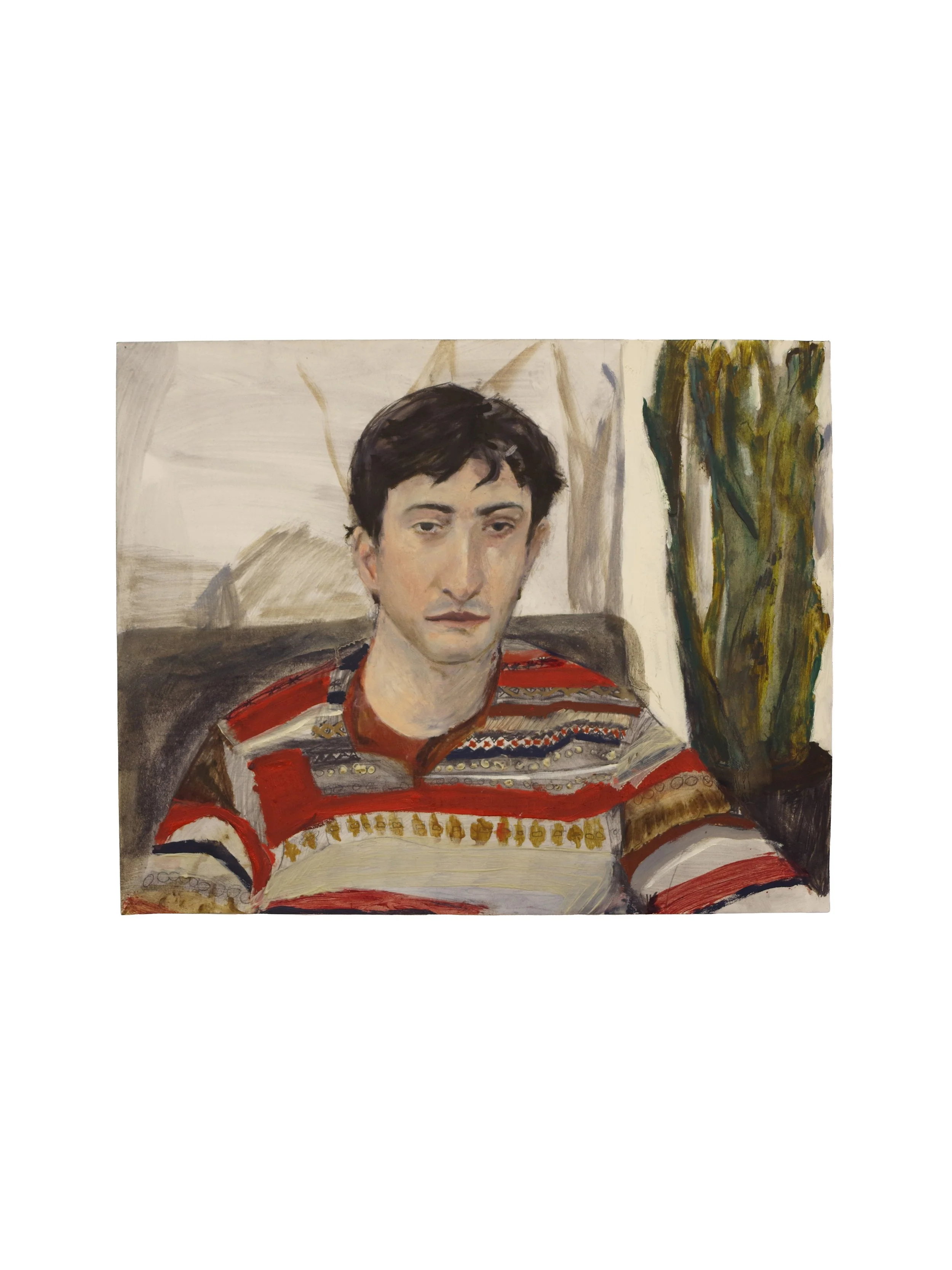

"Izzy", Oil and Graphite Materials on Paper, 16 x 20 inches, 2025

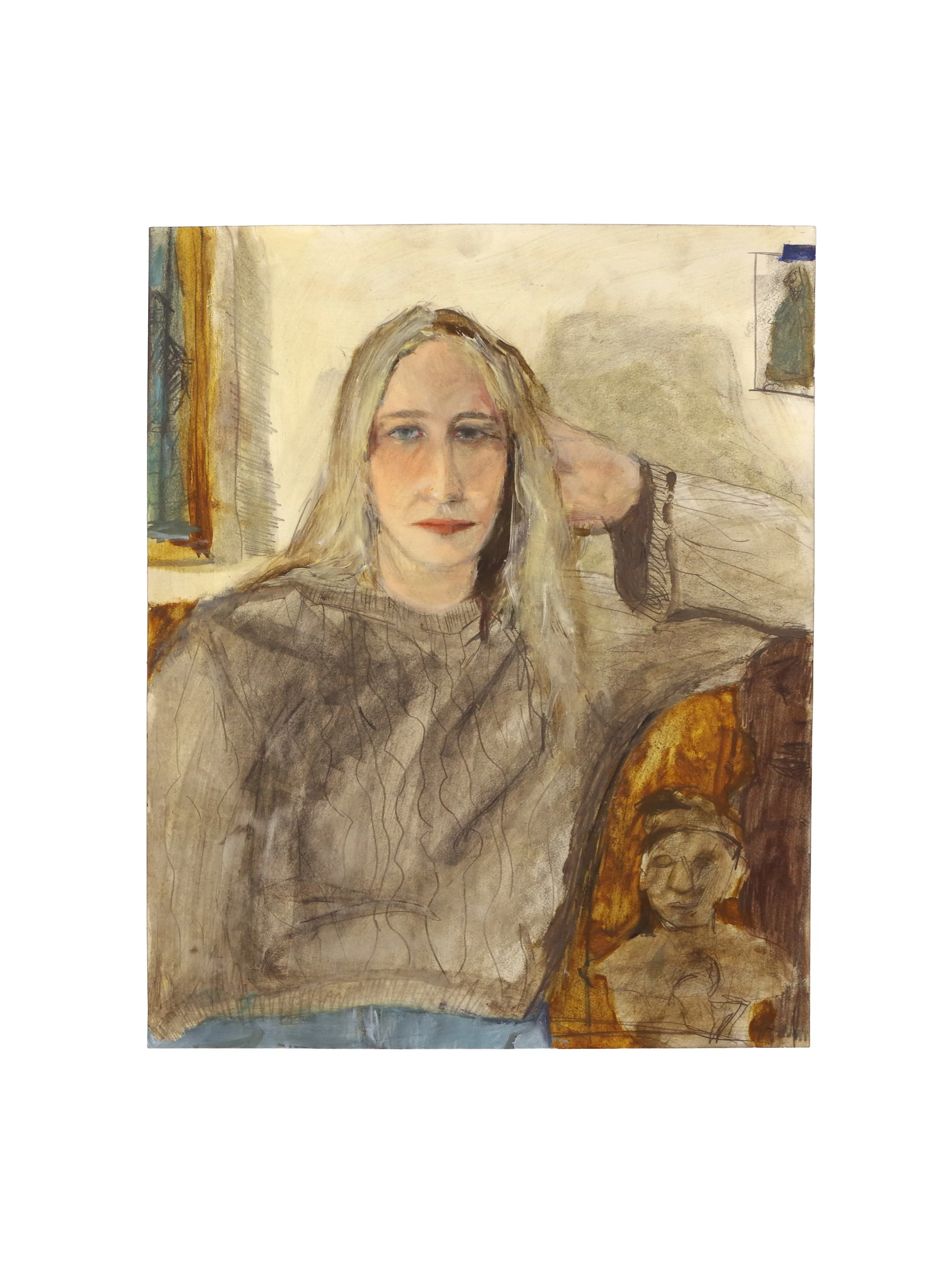

"Cameron", Oil and Graphite Materials on Paper, 28.5 x 19.5 inches, 2024

"Jinho in Button-down", Oil and Graphite Materials on Paper, 24 x 20 inches, 2024

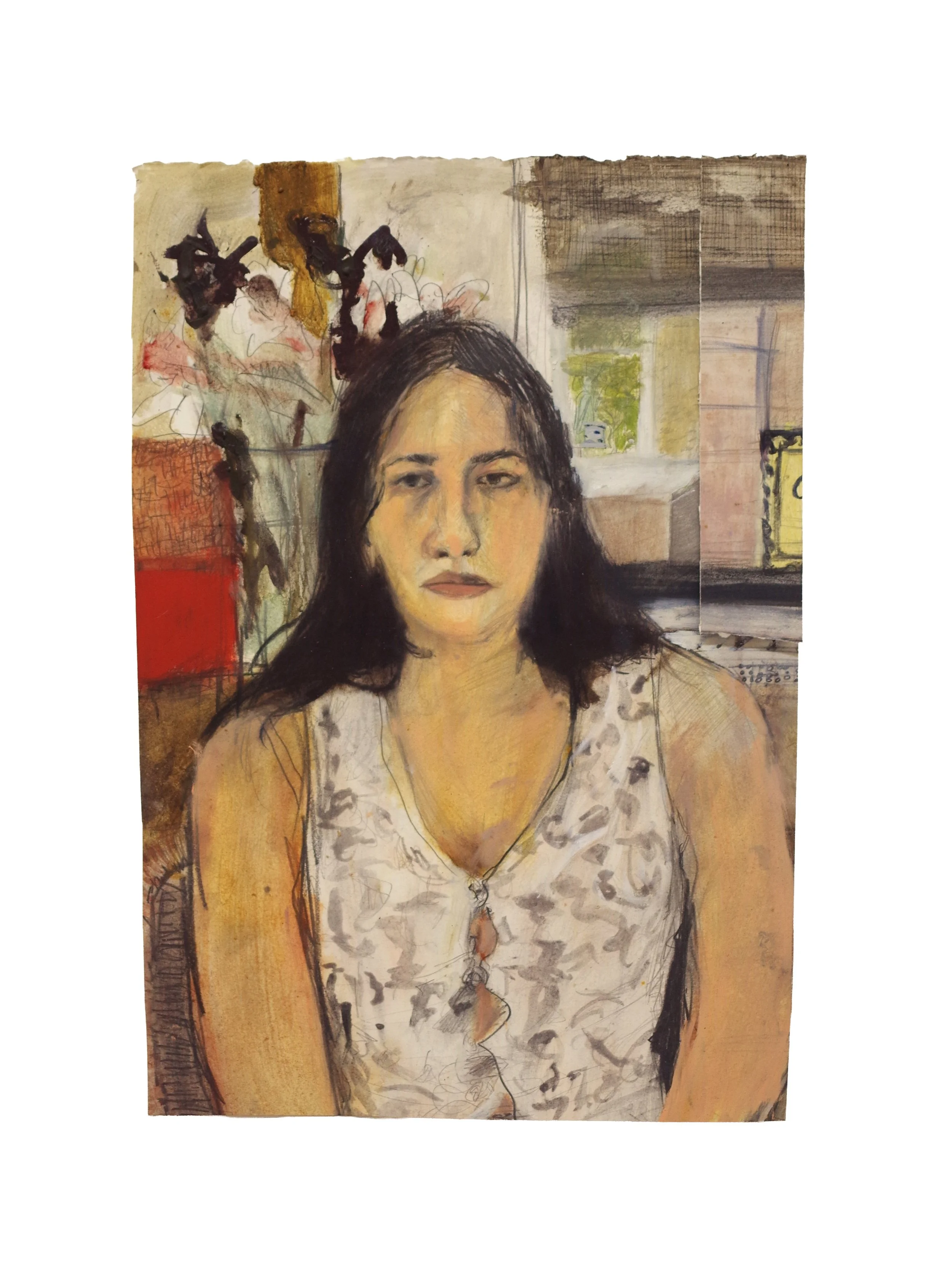

"Isabel in Chinatown", Oil and Graphite Materials on Paper, 21 x 14 inches, 2025

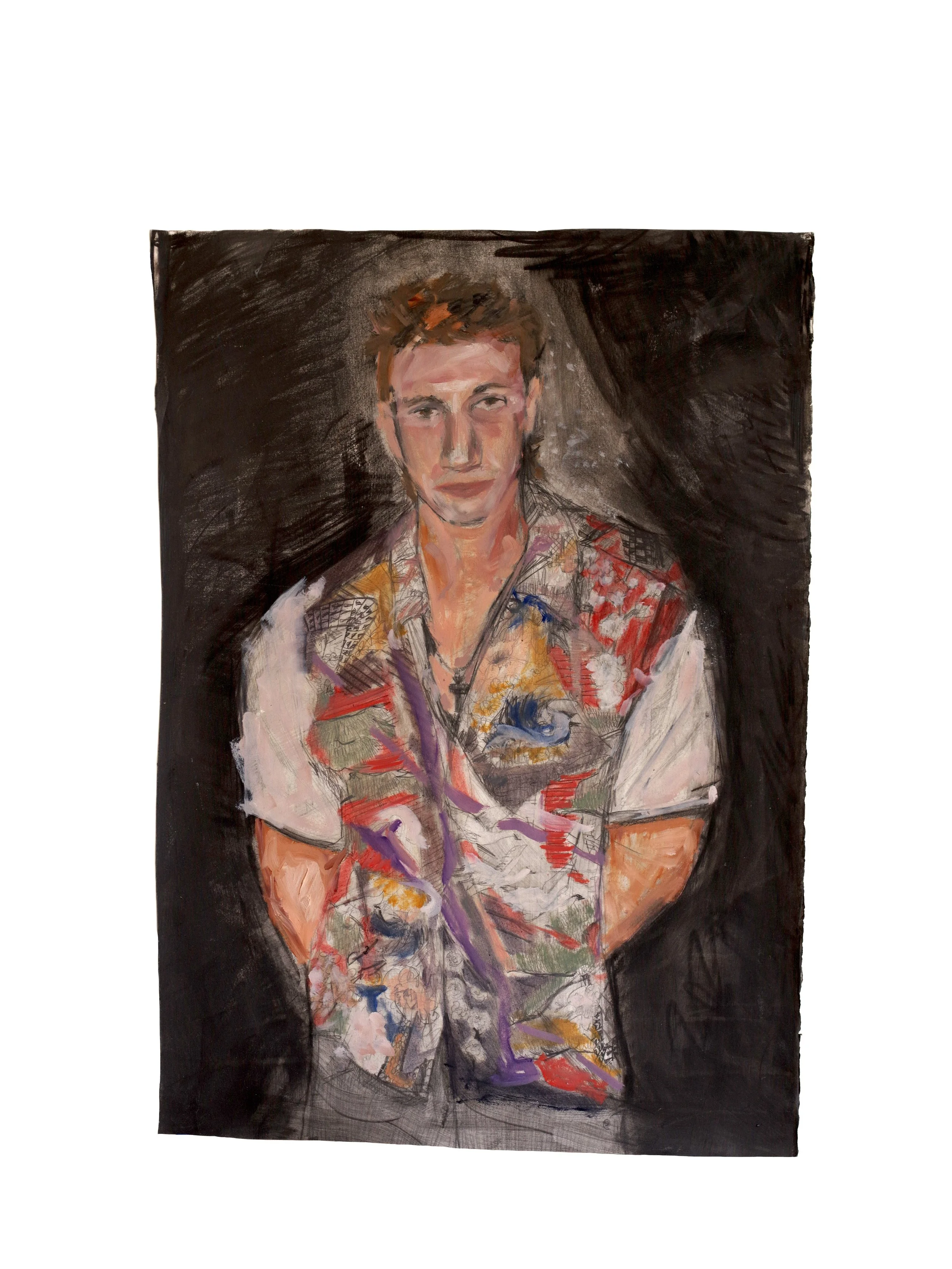

"Michael in Japanese Button-down", Oil and Graphite Materials on Paper, 25 x1 6 inches, 2025

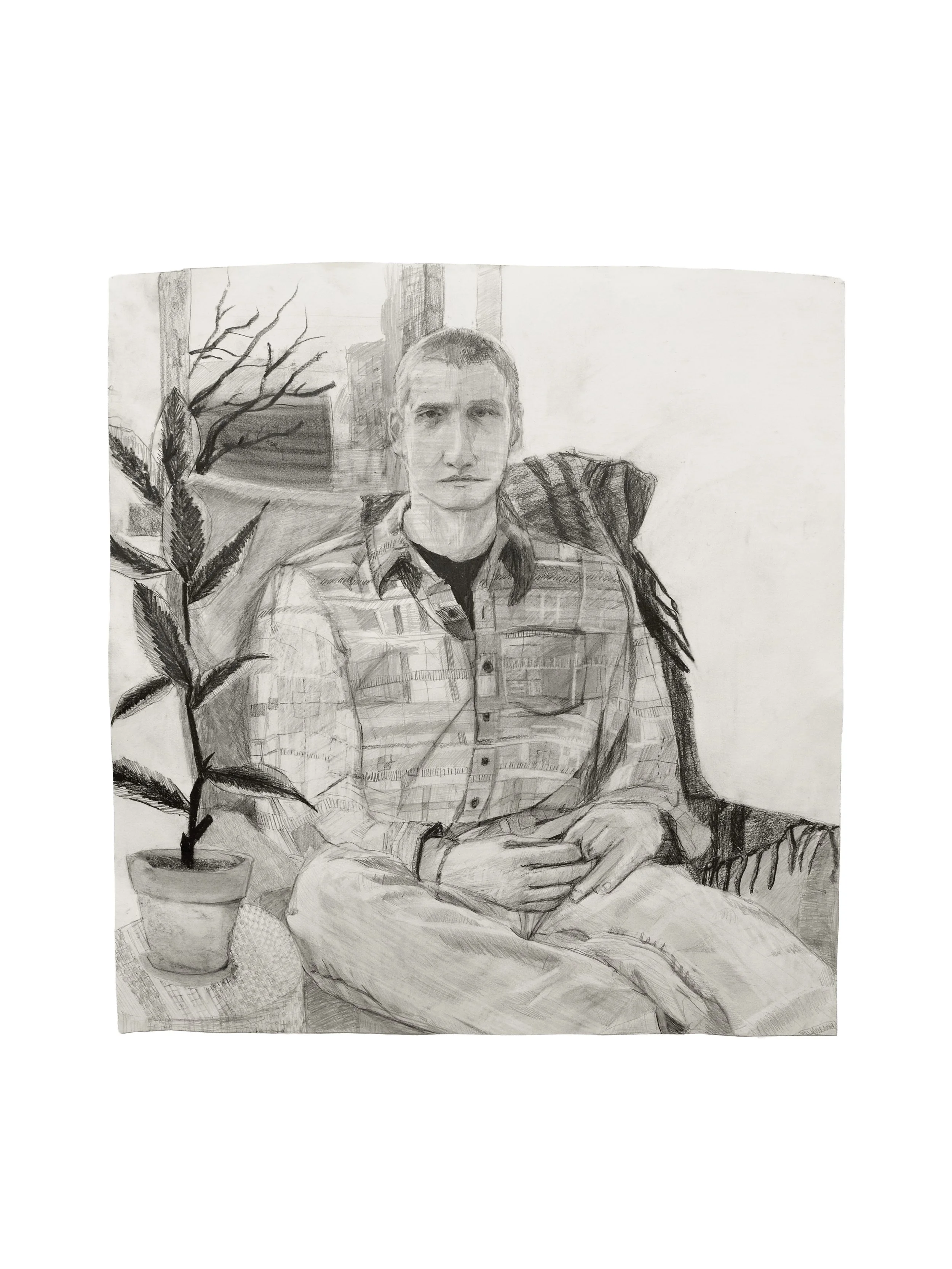

"Wally", Graphite Materials on Paper, 24 x 22 inches, 2025

"Grace", Graphite Materials on Paper, 20 x 16 inches, 2025

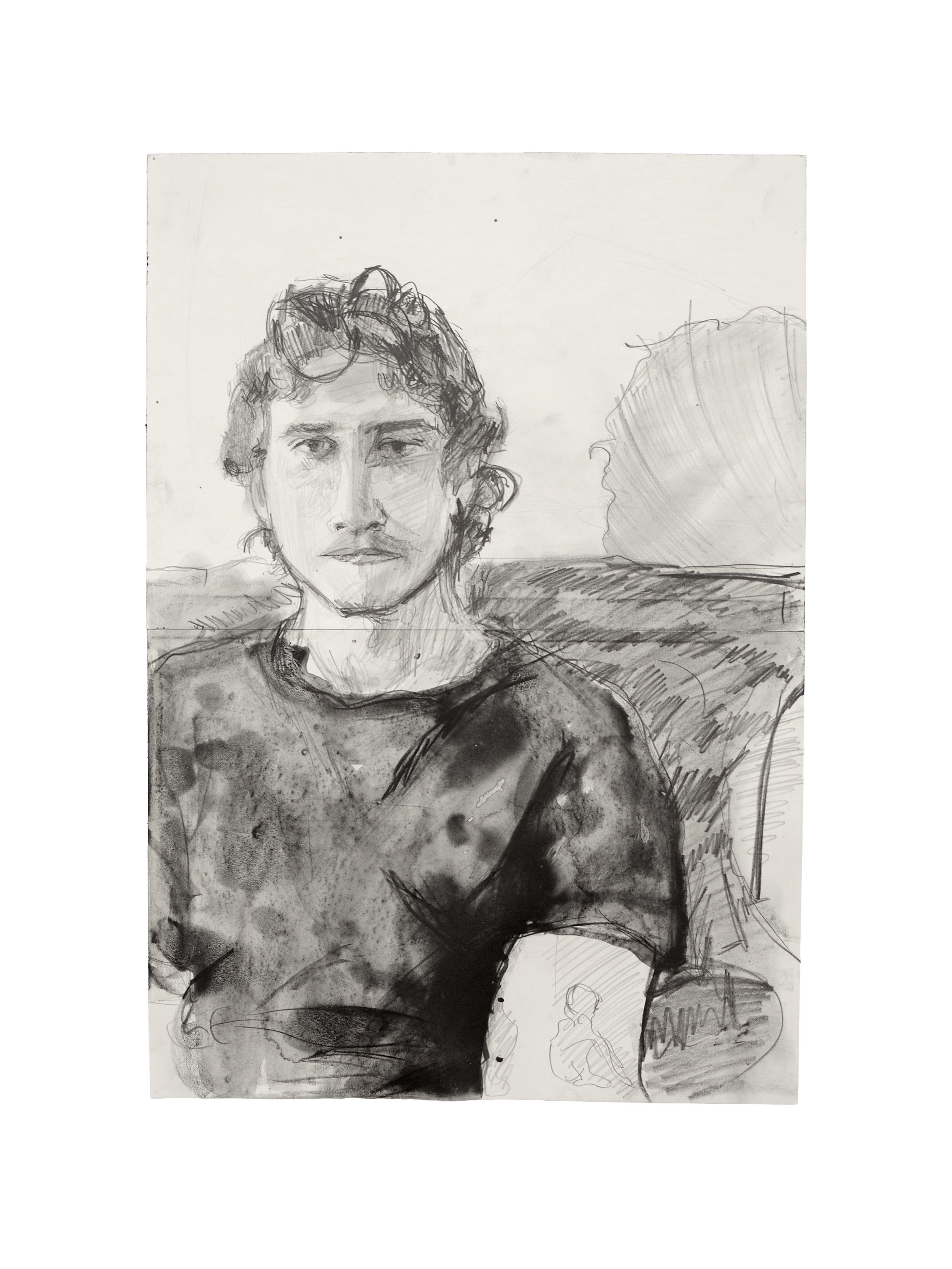

"Tadeo", Graphite Materials on Paper, 20 x 14.5 inches, 2025

"Cass", Oil and Graphite Materials on Paper, 16 x 20 inches, 2024

"Christopher", Oil and Graphite Materials on Paper, 16 x 20 inches, 2024

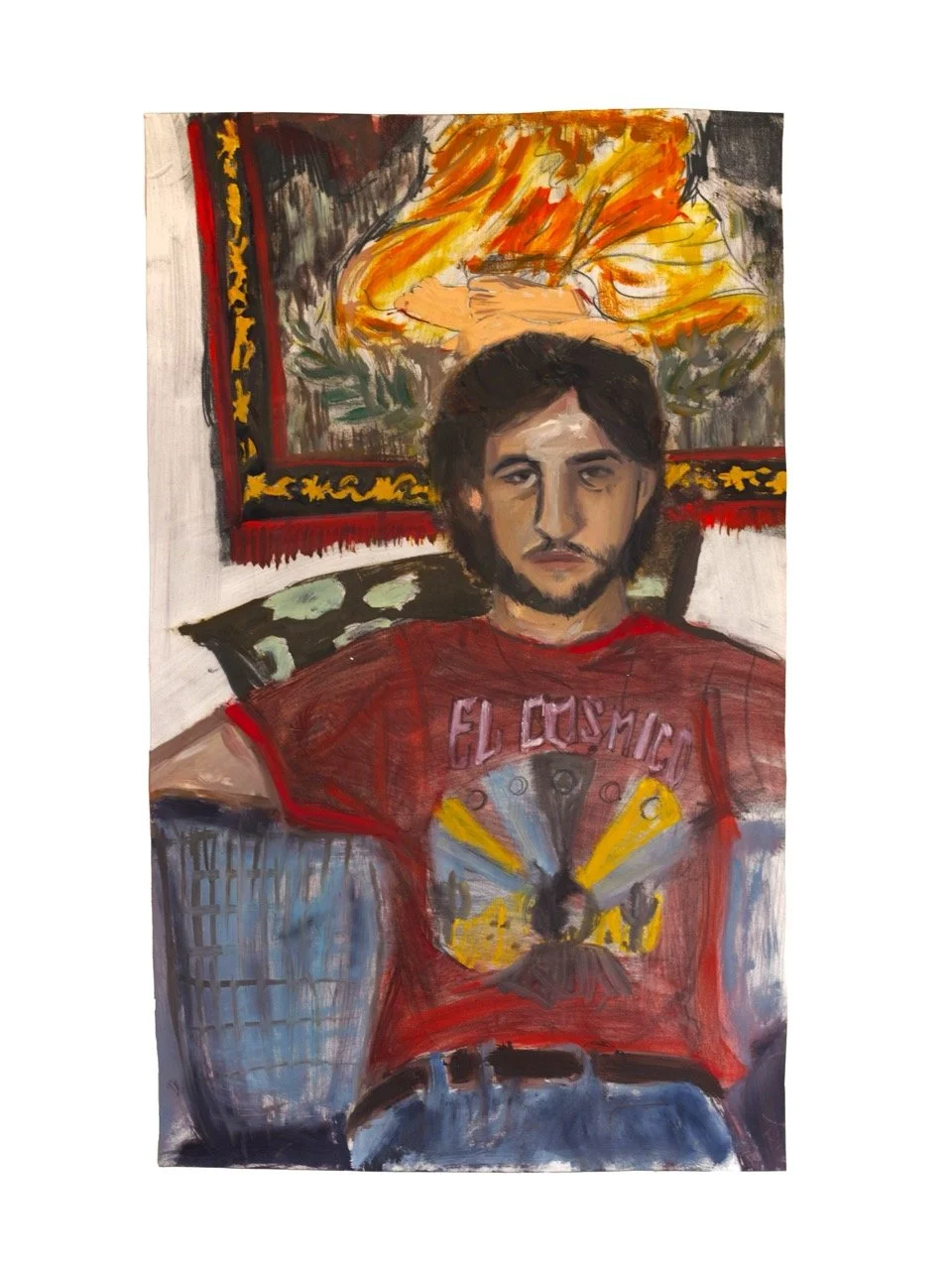

"Andrew at Budda’s Feet", Oil and Graphite Materials on Paper, 30 x 18.5 inches, 2024

"Scott with Monkey", Watercolor on Paper, 20 x 14 inches, 2025

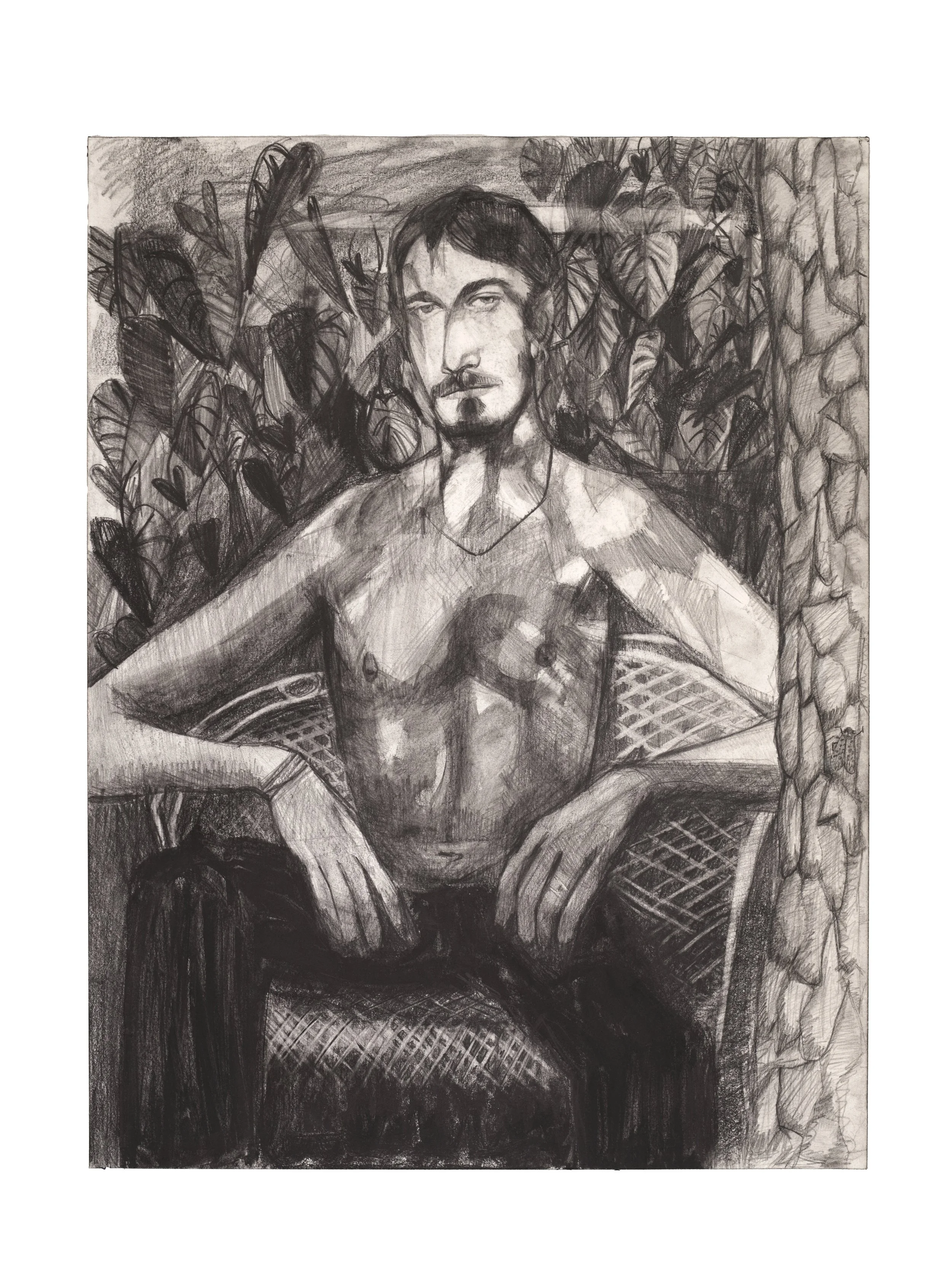

"Self in Foliage", Graphite Materials on Paper, 24 x 18 inches, 2023

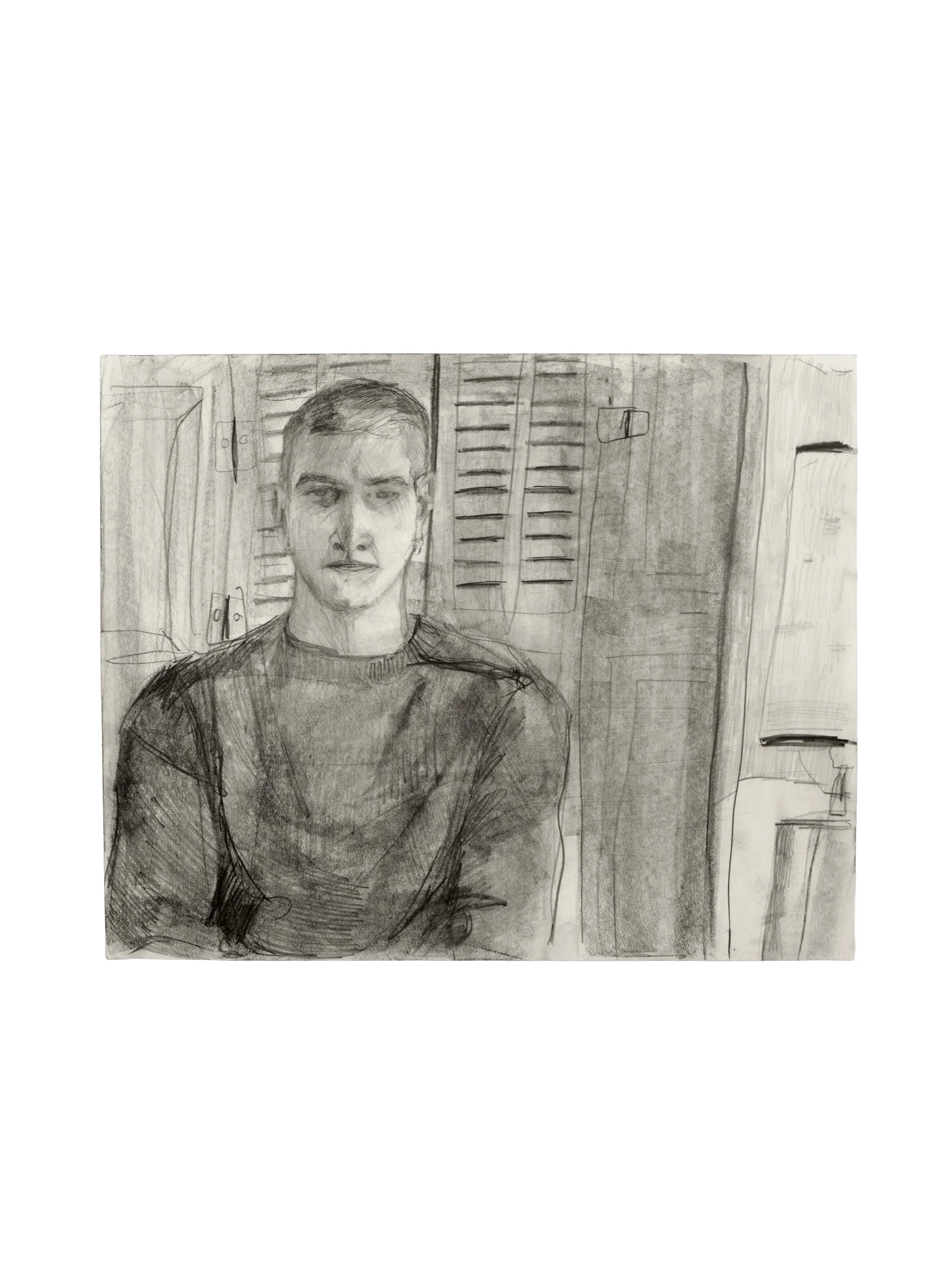

"Michael in Livingroom", Graphite Materials on Paper, 20 x 16 inches, 2025